Imagining AI - Babbage & Lovelace

Humans have always loved automated machines

As far back as ancient China, Greece and Egypt, we've created ingenious animated mechanical inventions which could move like us or perform simple tasks.

But who first imagined a machine which could think like us?

Discover the story of early computer pioneers Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace in their own words, through notebooks and manuscripts.

Part of Imagining AI from Oxford Maths, September 2022.

Difference Engine

Charles Babbage (1791-1871) – engineer, mathematician and economist – designed one of the first machines we would recognize as the ancestor of a modern computer.

He called it the Analytical Engine.

But his earlier designs – his Difference Engines – were much simpler.

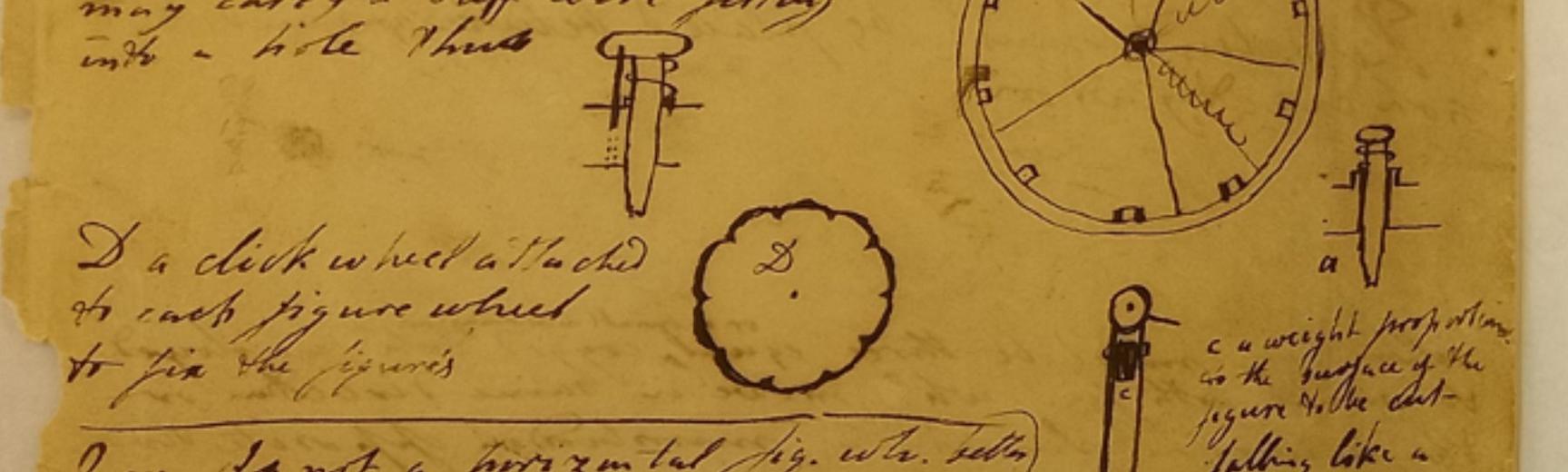

Parts of Difference Engine, by Charles Babbage, c. 1822-30 (Inv 94229)

The Difference Engine was a visionary machine intended to take the tedium out of everyday adding and multiplication tasks, using metal wheels and levers to store numbers and make calculations.

Babbage said his light-bulb moment – the idea of building an engine "powered by steam" to make long, tedious calculations – happened during a conversation with the astronomer William Herschel.

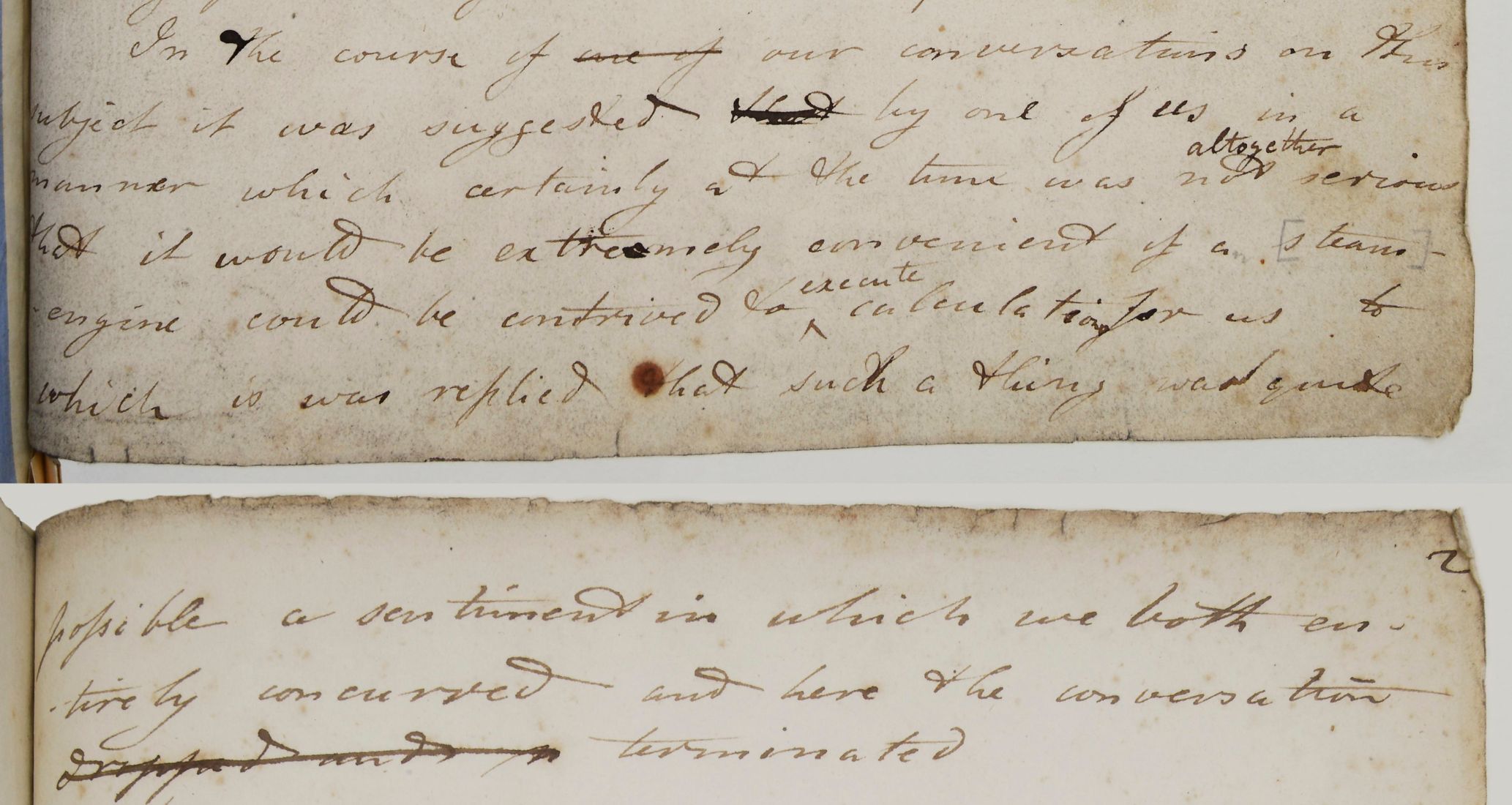

MS Buxton 7 34 f 1r a (Conversation with William Herschel)

In the course of our conversations on this subject, it was suggested by one of us, in a manner which certainly at the time was not altogether serious, that it would be extremely convenient if a steam-engine could be contrived to execute calculations for us, to which it was replied that such a thing was quite possible a sentiment, in which we both entirely concurred, and here the conversation terminated.

Source: Charles Babbage, 1822 MS Buxton 7.34

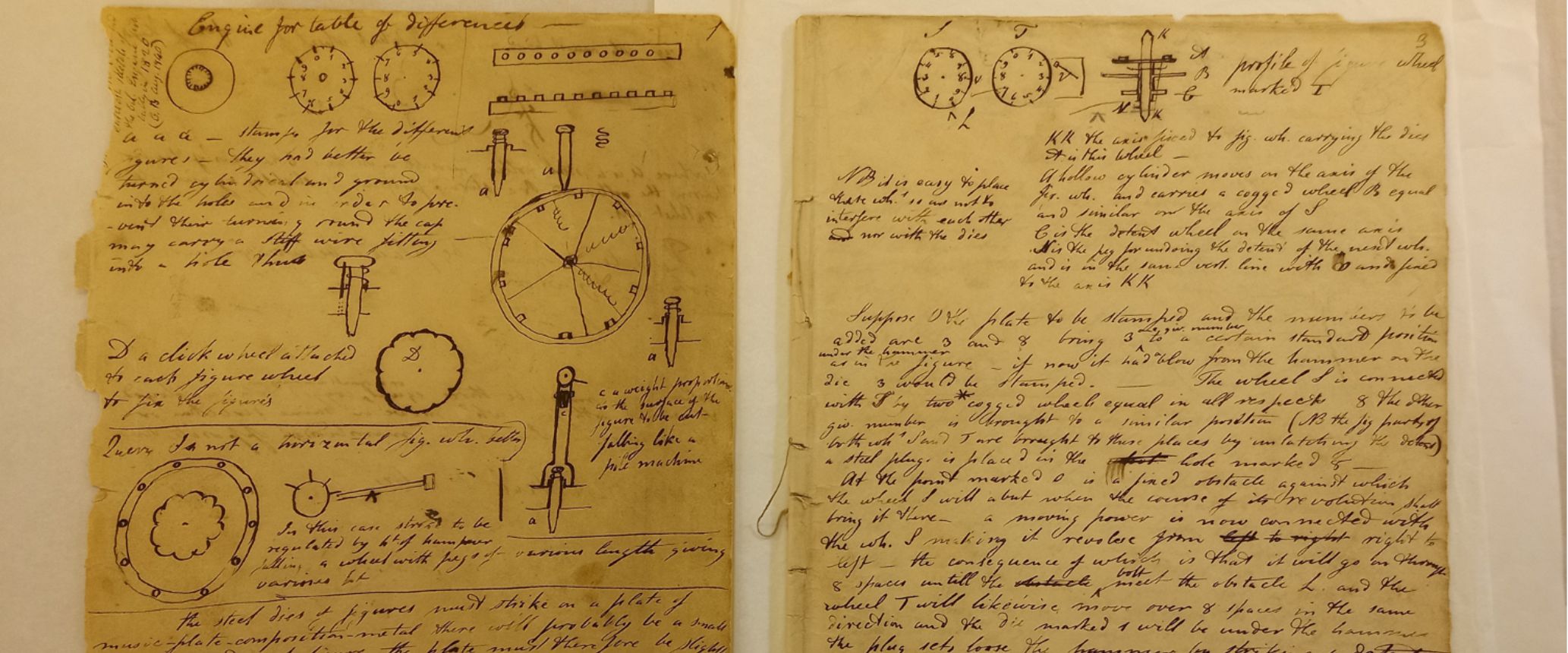

These are some of Babbage’s earliest, hand-written notes on plans for his “engines”.

His extensive notes and drawings show how he thought through all the practical details of how to build it – and he investigated many existing technologies. On this page you can see he is using ideas from music printing with “music-plate-composition-metal” in his design of a printer for his computer.

Charles Babbage 1822 MS Buxton 9 2 1r 2r

Although he created a number of different prototypes of the Difference Engine – we have some early trial pieces here in the Top Gallery – the full machine was not built in his lifetime.

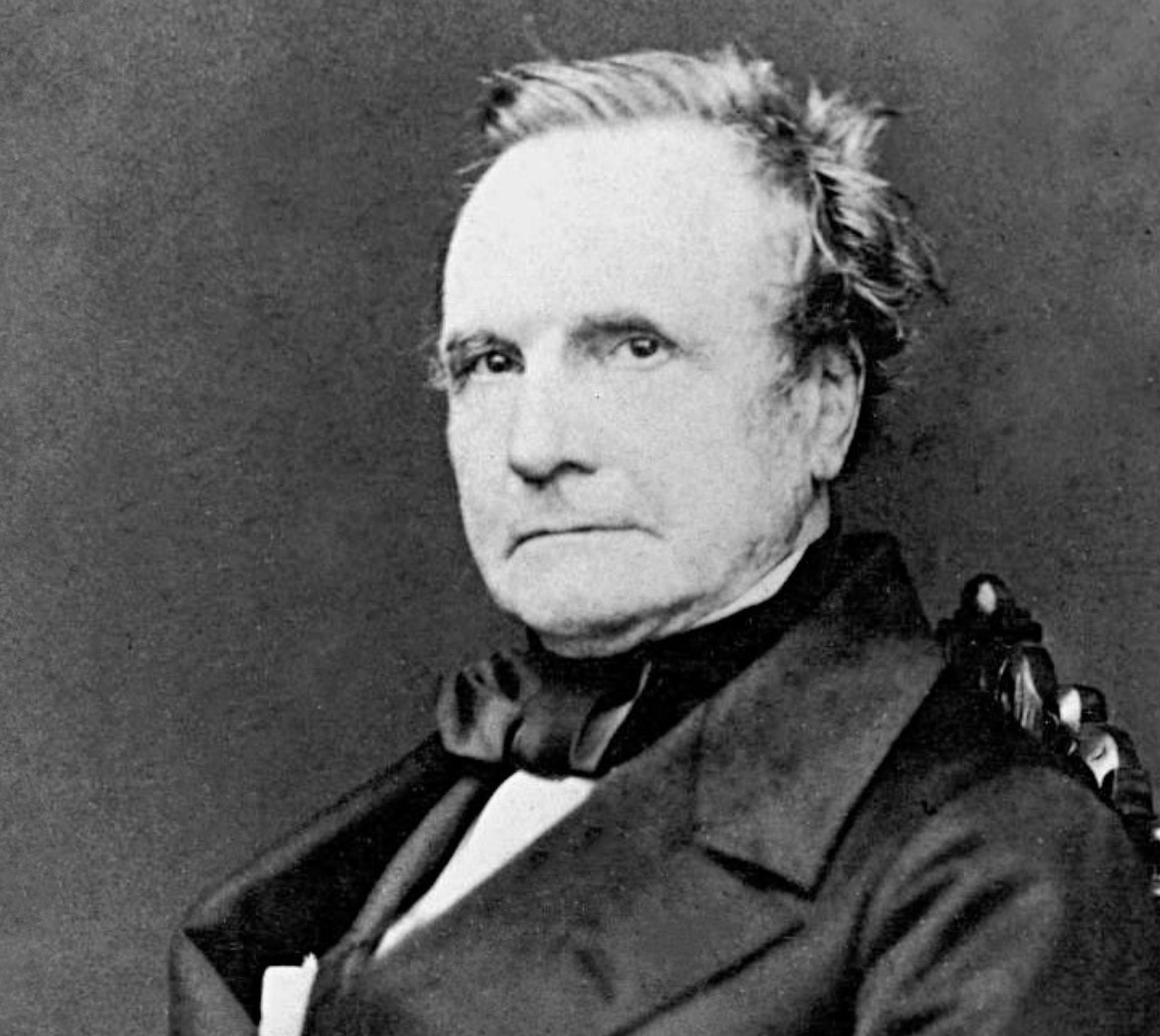

Charles Babbage, 1860

The sheer scope and complexity of his ambition – combined with a single-minded, straight-talking personality – ended up alienating his craftsmen, engineers and funders.

But we do know he was right.

His contemporary Pehr Scheutz successfully built a much simpler version, which was used in census calculations. And in 1991, the Science Museum in London used Babbage’s designs to build a fully functional Difference Engine.

Charles Babbage's next – and most ambitious – idea was to build a mechanical ‘brain’.

Analytical Engine

Babbage was fascinated by the limits of what mechanical technology could do. He believed it was possible to build a machine that could, in principle, calculate anything.

His Analytical Engine – had it ever been built – would have been the first operational, general-purpose computer.

It would also have been powered by steam, the size of a factory – and by modern standards, very slow.

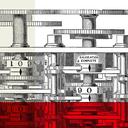

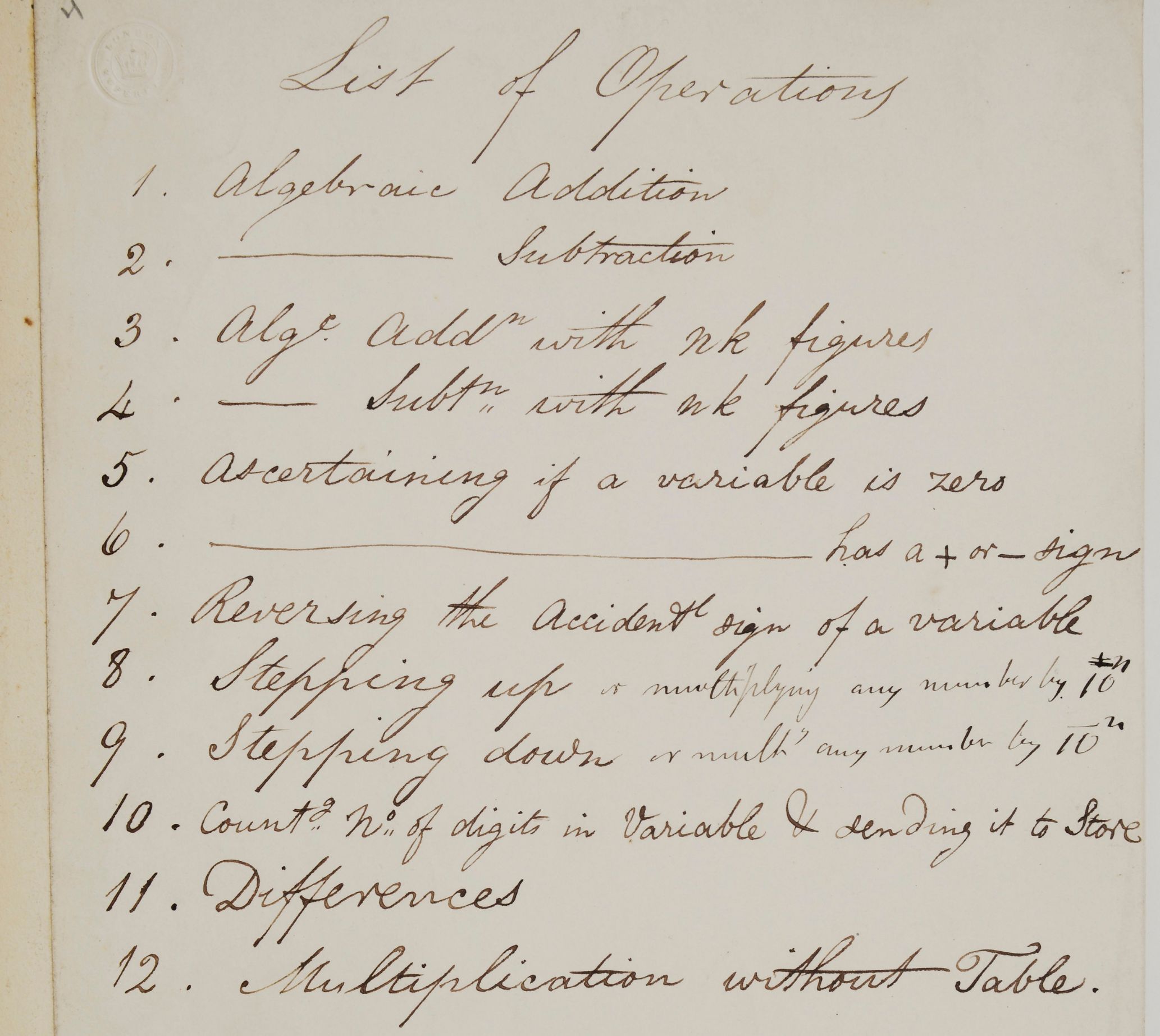

Babbage understood that his computer would need to be able to carry out this 'List of Operations’. Modern computers use exactly the same list of instructions.

Charles Babbage's List of operations, c. 1837, MS Buxton 7.6

While Babbage’s spiky personality may have rubbed his funders up the wrong way, he could still command a crowd. His ‘salons’ attracted the cream of society – including a young Ada Lovelace, who was captivated by his ideas.

Watercolor portrait of Ada King, Countess of Lovelace (Ada Lovelace)

Daughter of Romantic-era poet Lord Byron and his scientifically minded wife Isabella, Lovelace had studied mathematics to a high level. And in 1843, she collaborated with Babbage on a description of his unbuilt Analytical Engine.

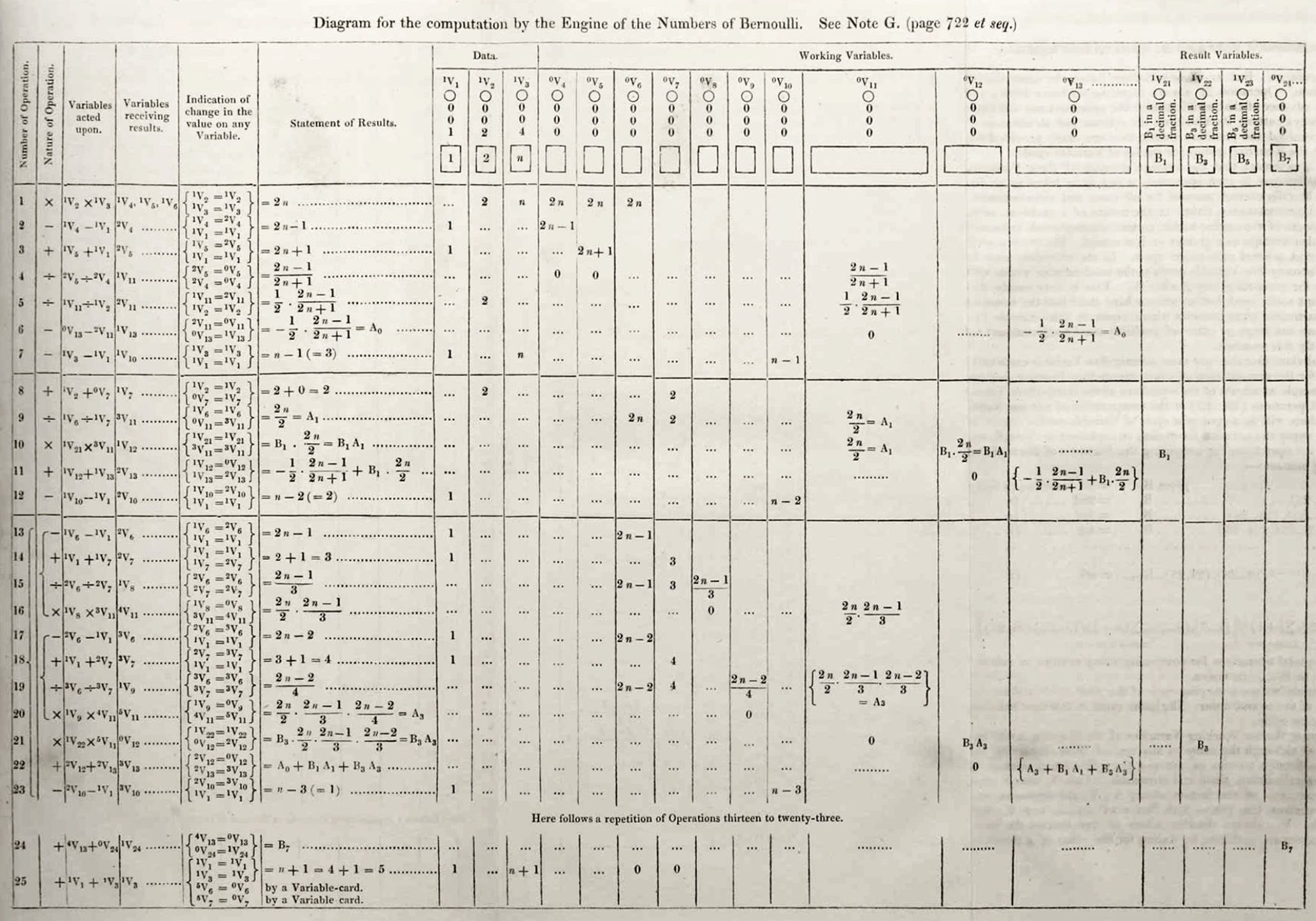

The article, which includes this diagram, shows every step in the calculation of a formula. It is sometimes – a little inaccurately – called “the first computer programme”.

Diagram of an algorithm for the Analytical Engine for the computation of Bernoulli numbers, from Sketch of The Analytical Engine Invented by Charles Babbage by Luigi Menabrea with notes by Ada Lovelace

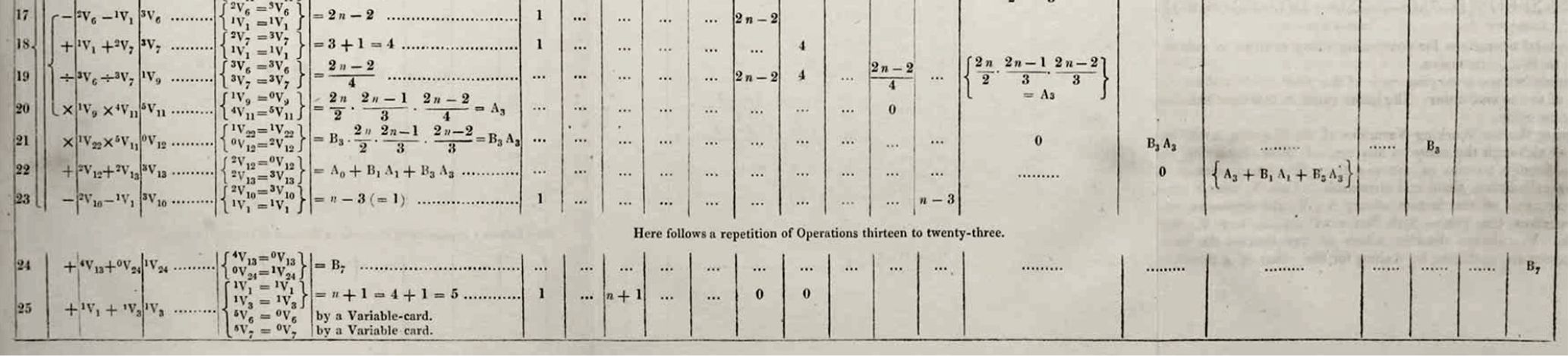

What Ada describes as “here follows a repetition ...“, we would now call a loop.

Diagram of an algorithm for the Analytical Engine for the computation of Bernoulli numbers, from Sketch of The Analytical Engine Invented by Charles Babbage by Luigi Menabrea with notes by Ada Lovelace

Beyond Babbage and Lovelace

But computers can’t think for themselves – they have to be programmed by a human being.

As Ada Lovelace wrote:

The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform.

Nearly two hundred years later, twenty-first century programming languages combine ordinary language, logic and mathematics to give computers precise, unambiguous instructions.

And modern Artificial Intelligence (AI) programmes – far more complex and sophisticated than anything than Lovelace or Babbage could imagine – produce results that their programmers could never have predicted.